Mora in his studio. Photo provided by the artist.

Published in Newcity (April 2022).

To get to Joseph Josué Mora’s studio you dive off of Pershing Avenue into an unadorned parking lot in McKinley Park, down the street from where he spent his first years in Chicago. From the outside, the building is repetitive and foreboding, but folded into a west-facing wall is Mora’s uniquely warm studio, which he shares with Marimacha Monarca Press, Nicole Marroquín, and his partner, also an artist, Sarita García. It’s fitting for Mora to be tucked away, yet surrounded by companions and collaborators.

As a DACA recipient, Mora’s work is inundated with the sense of limbo. In some ways the tension is explicit: He is not quite a U.S. citizen, but he’s not quite not. He is distinctly Mexican American, an identifier that itself combines two states into one word. But there is also a quieter tension that he wrestles with: one between community art and fine art.

“I want to make my work accessible to people who might not see this type of work,” he says. So he sells zines and works in afterschool programs. He teaches students about his influences, like Sol LeWitt and Maria Gaspar. But Mora has other, sometimes competing, ambitions.

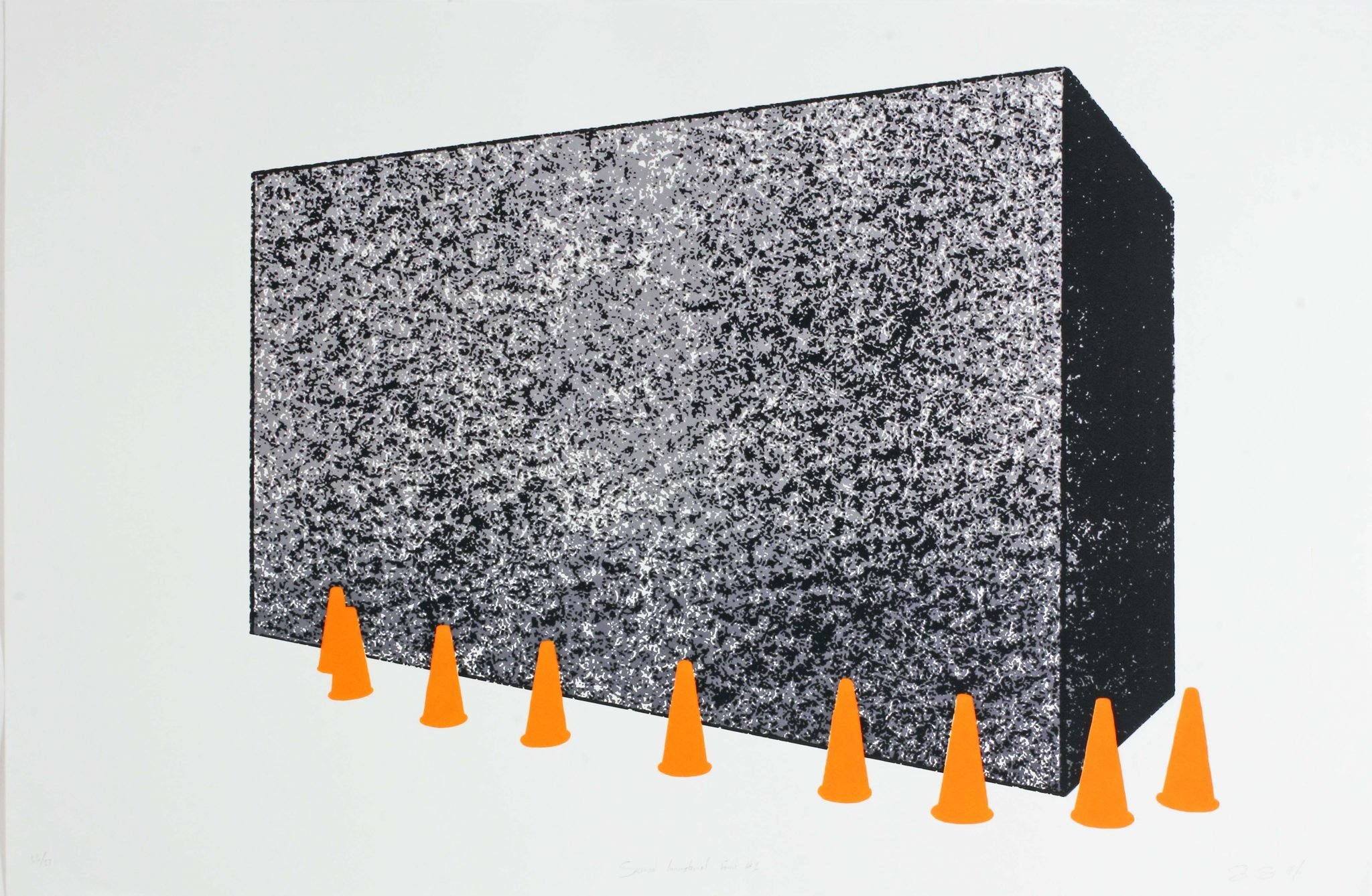

“Secured Immaterial Forms #1”

“I worry that it’s inaccessible,” he says of a twenty-six-inch-by-forty-inch print on the wall called “Secured Immaterial Forms #1.” “It’s minimal and conceptual, so it’s not as attractive as a zine.” That may be so, but it has at least as much to say.

“Secured Immaterial Forms #1” is one in a six-part series that Mora began during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. Mora was struck by the way policemen on Chicago’s Magnificent Mile staunchly guarded retail shops rather than protecting people. In the print, a dense-as-concrete block stands ominously, surrounded by nine bright orange traffic cones. The cones, he explains, are policemen.

Half a year later, on January 6, 2021, Mora watched rioters overtake the U.S. Capitol. He immediately knew that this incident was in conversation with the past summer’s protests—three new designs were born. In one, “Encouraged Ingress #1,” a dome sits where the block once was, printed with the same rough texture. Nine orange traffic cones lay on their sides, haphazardly scattered around it.

3-D cones in Mora’a studio.

Mora is currently working on taking this design further by creating concrete molds and 3D-printing traffic cones to sell as a boxed set. The cones are thumb-sized and playful, the concrete is, well, concrete. He’ll package the set in foam and construct a fine-art crate to house it all, alluding to his skills as a professional art handler.

By day Mora works as a gallery technician at the SITE galleries. “The art handler is supposed to be invisible,” Mora says. “I started to associate it with undocumented immigrant labor, the workers behind the fancy restaurant, the field workers, the people who clean at 1am.”

Art handing Polaroids, 2021-22. Provided by the artist.

He also keeps a visual diary of unseen forces that, quite literally, hold the SITE gallery together: “L” hooks protruding from the wall, painter’s tape, laser levels. In a future project, Mora plans to dig deeper into the analogies offered by his day job; a pillar of dried plaster to one is a recorded history of labor to Mora.

As I pack up to leave, Mora gifts me a zine called “UNDOCU-ALLY,” full of tips and anecdotes about the undocumented population in America. A pocket-sized reminder that regardless of where Mora’s art takes him, he’s never close, and never far from home.